- Home

- Vassilis Vassilikos

Z, 50th Anniversary Edition

Z, 50th Anniversary Edition Read online

VASSILIS VASSILIKOS

Translated from the Greek by Marilyn Calmann

New York • Oakland

Z

50TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

Copyright © 1966 Vassilis Vassilikos.

English translation © 1968

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Inc.

Preface Copyright © 1991 Vassilis Vassilikos.

First Seven Stories Press Edition January, 2017

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

ISBN 9781-1-60980-712-2 (paperback)

ISBN 978-1-60980-713-9 (epub)

SEVEN STORIES PRESS

140 Watts Street

New York, New York 10013

Printed in the U.S.A.

Contents

Acknowledgments

Preface to the new edition: 25 Years Later

Part I: An Evening in May, From 7:30 to 10:30

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Part II: A Train Whistles in the Night

Part III: After the Earthquake

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Part IV: Apologias

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part V: One Year Later

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Mary Manheim

for inestimable help with the English version of my book.

I would also like to thank

Mary McCarthy, James Merrill,

Professor Joseph Frank of Princeton University,

and Ralph Manheim.

Also the Ingram Merrill Foundation,

whose generosity left me free to

work on the Greek text in Greece and

on its translation in exile

Preface to the new edition: 25 Years Later

Before writing Z in 1966, I wrote a long preface which was published many years later as a separate book under the misleading title, Diary of Z. Those who hoped to find in this near-novella the background to the book or the underside of the Lambrakis affair were disappointed miserably. Because what is described in the Diary are the difficulties and inhibitions of the author.

Considering, as I did in 1966, Z to be an accusatory book, I also considered the long preface to weaken it. Because it emphasized the subjectivity of Z, which was a j’accuse against the parastate of the Right. Recently, in a republication of Z in Greek, I incorporated the Diary as its first section. Time had passed and taboos had collapsed on both sides. The writer could fearlessly show his cards.

Criticism in Greece, before the colonels’ coup in April 1967 (the book having been published originally in November 1966), was concerned initially with the facts of the case (as the trial of the murderers of Lambrakis was taking place then, at the same time, in Salonika). My book was considered an almost journalistic narration. No attention was paid to its literary qualities. That it was “inaccurate” in relation to the facts (which was the view of the official Right) led one reviewer to write that “figs do not ripen in May.…”

Much later, after the collapse of the dictatorship, the only correct review was written by Andreas Karandonis, the dean of Greek critics, who viewed the book not as left-wing propaganda, but as the result of proto-Christian faith. (The Lambrakis-Christ parallelism.) This is a view to which I can nearly agree. Before Z was published in book form, it was serialized in the magazine Tachydromos. I can still remember my joy (the only real joy) when at the stadium I saw a sports fan passionately reading the current installment of Z instead of watching the soccer game.

When I was asked in an interview why I wrote Z, I responded provocatively: “In order to influence the members of the jury.” The fact, however, that I managed to write it I owe to another writer, Truman Capote. His book, In Cold Blood, had influenced me deeply. I was never able to write something if there were no model on which to base myself. Past models were Gide, Camus, Kafka, Ionesco. Then Capote. Afterwards Garcia Márquez, Claude Simon. And others; their numbers are legion.

The second career of the book began the moment the truly remarkable Costa-Gavras film was made. With Costa-Gavras I participated in the more general synthesis of the film, rather than on the script. As there was no chance of Z being filmed in Greece, we decided to excise the lyrical parts of the book. We also decided against the use of documentary material. Costa also saw his film as an accusation, not against the parastate of the Right, but specifically against the usurpers of authority, the colonels. And with clever editing of time, at the end of the film, the viewer is left with the impression that the crime was committed during their rule. The dissemination of the book was much helped by the film, because viewers wanted to learn more about the protagonists. This, however, created a problem for me: I was labelled a “political writer,” although I had never been one. Even now, especially in France, they ask me about the role of engagement (commitment) in literature. I find this terribly unpleasant because I believe that all art is committed from inception, while not everyone who claims to be committed is necessarily an artist.

A word on the translation. Z reached my hands, during my exile in Paris, in a miserable English translation which I had to redo in its entirety. The translator, blaming the dangers she was facing from the colonels’ regime, delivered the text under a pseudonym and vanished. Fortunately there were friends who helped me. Mainly Mary McCarthy and James Merrill. She went through the entire narrative part and he looked at the lyrical sections. Ralph Manheim and his wife, the translators of Brecht into English, also provided much help.

I was not present when the film was shown in America. Imitating Sartre, I did not want to set foot in

America because of the war in Vietnam. Something which I have paid for dearly, since this was the reason for my exclusion from the American publishing establishment for many years. Until today. Nevertheless, I do not regret that decision. It was correct.

What happened to the protagonists in the book? The examining magistrate became President of the Republic (1985–1990), the general died, and the parastate, having flourished during the junta years, afterwards disappeared. One day, asking directions to a street in the Toumba area of Salonika, I realized that the man I was asking, from inside my car, was no other than Yango (i.e. Kotzamanis in the real world, one of the murderers of Lambrakis). Fortunately, he did not recognize me—in the meantime, fifteen years had intervened—nor did I become fully conscious that it was him until I was quite far away. I must say that he was very polite and eager to assist me.

I think the fact the crime took place a few meters away from my old neighborhood in Salonika was decisive. The city itself, which had inspired in me so many texts (The Leaf, The Photographs, Outside the Walls) could not have left me indifferent. But there was a man, Demetris Despotides, my political instructor, a kind of precursor of Gorbachev, who is now dead and who played an important role. I mention him repeatedly in the Diary. Demetris brought to me secretly the proceedings of the investigation from which I drew my material.… And it was to him that I first read some excerpts at the loft of the publishing house he founded, Themelio. This preface is dedicated to his memory. For Demetris, who hated sentimental “folklore,” whether of a political or any other kind, what was paramount was to demonstrate the mechanism of the crime. That there are no murderers by birth, but that society itself breeds them. This is why Czechs, Lebanese, Argentines were recognized in the film Z. In America, the film was taken to involve the Kennedy affair.

In my notes (from the first writing of Z) I also discover the following clipping from a newspaper of that period: “Washington. May 29, 1963. Wire Services. President Kennedy received at the White House best wishes by reporters on the 46th anniversary of his birthdate today, smiling and joking. ‘You look a little older today,’ said the President, surprising press representatives before they had a chance to wish him happy birthday. In all other respects, President Kennedy followed his regular schedule of activities.” Six months later he went, too, to meet Lambrakis. However, twenty-five years later, we are still awaiting the novel about Kennedy from America.

—VASSILIS VASSILIKOS

Paris

February 15, 1991

TRANSLATED FROM THE GREEK BY YIORGOS CHOULIARAS

PART I

AN EVENING IN MAY, FROM 7:30 TO 10:30

Chapter 1

The General looked at his watch as the speaker of the evening, the Assistant Minister of Agriculture, was winding up his address on the methods of fighting downy mildew:

“In summation, I recapitulate: the outbreak of the Peronosporaceae, or downy mildew, is prevented by spraying the grapevines with a solution of copper salts and especially copper sulphate. The classic solutions are the bordigalian and the burgundian fungicides; and it is called burgundian because it was first concocted in French Burgundy, from whence originate, believe me, the truly superb wines of the same name. The first, the bordigalian, is composed of a one-to-two percent solution of copper sulphate in water, the acidity whereof is neutralized by the addition of lime. The latter differs from the former insofar as use is made of Solvay soda instead of lime. These classic concoctions are modified by adding highly viscous substances to prevent the mixture from being washed away easily by the rain.”

The General shifted his legs, setting the right one over the left, impatient with the length of the Assistant Minister’s peroration.

“Also,” the Minister continued, taking a swig of water from the murky glass the Secretary General had had the usher bring (it was May 22, 1963, for a whole week the heat had been stifling, and if the Minister’s tongue were dry, his words might stick to each other), “powders with copper salts as a base are used because they are easier to work with. Three sprayings per year are carried out by means of special instruments called sprayers: the first spraying when the shoots attain a length of twelve to fifteen centimeters; the second slightly before, or slightly after, the blossoms appear; and the third a month later. However, when it is a damp year, and if the locale is damp, spraying must occur more frequently.”

The rest of them, prefects and commissioners of the police department, had begun to feel sleepy. A good fellow, the Assistant Minister, but he spoke as if testing his forensic skill for the first time. He spoke in an overly scientific way, and besides, what did these officials care about downy mildew! The Assistant Minister, who did care, failed to realize that in Macedonia and especially in Salonika, where he was presently speaking, the vineyards were not as important as in his home territory, the Peloponnese, his electoral district. Here they had tobacco, and he still hadn’t said the first word about that. On their level, they had managed things well: without knowing a thing about the subject, they had spread it about in their villages, districts, and prefectures that downy mildew was a disease brought directly from Eastern countries—thus enormously contributing to the anti-Communist movement in the area, because many villagers believed the rumor. Alas, not all. But the irresistible argument remained that the downy mildew oppressing their fields and withering their tobacco plants had appeared for the first time with Communism. They were of the same age. And in the pamphlets scattered from planes (which should have been spraying the tobacco fields instead) they had written in big red letters that Peronosporaceae was the disease of Communism.

Only the Directors of the Agricultural Bureaus of Northern Greece listened with attention, almost with reverence, to the flawless scientific analysis of their Assistant Minister. He continued:

“During the spraying process, the entire foliage of the vine must be well covered. The effect of the spraying is merely preventive and for this reason must never be neglected. Another genus of the Peronosporaceae family is the Plasmopara nivea, causing the Peronosporaceae of the shade plants. This too is controlled by being lightly sprayed with the bordigalian mixture. In concluding my present analysis of the methods of fighting downy mildew, I wish to thank you warmly for the attentiveness you have shown during this talk.”

A bit of faint-hearted applause was heard and the Assistant Minister got down from the rostrum.

Then the General rose. He waited for the Assistant Minister to pass into the auditorium, and then, turning his back to the rostrum and facing the middle-aged, fattish, bald prefects and those officers of the police department inferior to himself in rank, indifferent perhaps only to the Directors of the Agricultural Bureaus, he said:

“I too wish to take the opportunity to add a few supplementary remarks to what the Assistant Minister has so elegantly expounded to you. Of course I am going to speak about our own downy mildew, Communism. And it is a rare opportunity for me, who am in charge of the supreme administration of the police department of Northern Greece, at this moment when the highest officers of the government are before me, to say a few words about the ideological mildew scourging our land.

“Personally, I myself have nothing against the Communists. From the very beginning, from time immemorial, they have roused in me only pity. I have regarded them as lambs strayed from the right path of our Hellenic-Christian civilization. And I have always been ready to help them, guide them, bring them back to the straight and narrow path of national consciousness. For, as we all know, Greece and Communism are irreconcilable by their very nature.

“However, like downy mildew, Communism must be fought at least preventively. With Communism as with mildew, we have to treat conditions caused by a variety of parasitical toadstools. And just as the spraying of the grapevine in three stages may keep it from being attacked by downy mildew, just so the spraying of human beings with mixtures appropriate to the circumstances becomes indispensable. The schools are the first stage for this kind of spraying. The shoot

s—to use the Assistant Minister’s metaphor—have not yet acquired a length of more than twelve to fifteen centimeters. The second spraying—and my long-range experience at the head of the force can tell you that it is the most critical—takes place just before or shortly after the blossoms appear. Here, of course, I refer to the universities, to the workers, to the young people with problems. If this spraying is successful, it is very difficult, not to say impossible, for the sickness of Communist mildew to spread and by its corrosive influence wither the sacred tree of Greek freedom. The third spraying must occur a month thereafter, as the worthy Assistant Minister has emphasized. For this month substitute a period of five years and you will see that the same holds true here too.

“Conclusion: in this manner, the fertile fields of the Greek earth will nourish only good fruit, and the illnesses of our time—Communism and mildew—will vanish finally and forever. This is what I had to say to you to encourage you all in the difficult task of fighting both downy mildew and Communism.”

Tumultuous applause drowned the finale of his speech. The assembly was over. Prefects, commissioners, and directors got up, lit cigarettes, stretched themselves, and, following their superiors, prepared to leave.

At the exit the Secretary General approached the General with a spineless, fluid movement and shook his hand. “And now, where to?” he asked him.

“To the theater, the Bolshoi Ballet,” replied the General. “I have an invitation and I’ve got to go. Though I must stop first to pick up the Chief of Police, who …”

“They didn’t send me an invitation,” the Secretary General said suddenly, stopping in the middle of the long corridor that led to the broad marble staircase covered in red Persian carpeting.

“What an omission!” exclaimed the General, though he had little interest in the Secretary General. Secretaries general came and went, depending on what party happened to be in power. In the course of his long career he’d known dozens of them.

Z, 50th Anniversary Edition

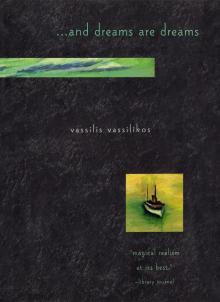

Z, 50th Anniversary Edition ... and Dreams Are Dreams

... and Dreams Are Dreams